The History

of Visual

Communication

The Chinese and the Japanese, the Egyptians and the Mesopotamians

Ideograms, on this website, are examined with specimens from three major ancient cultures: Chinese, Egyptian and Mesopotamian. While it is under argument whether Egyptian hieroglyphics precede Chinese ideograms or vice versa (both dating back to circa 4000 BC), the Mesopotamian ideogramatic system called cuneiforms can be dated back to circa 3000 - 3500 BC. Added should be that, while the Mesopotamian and Egyptians cultures have not survived in their ancient formats into the present day, the Chinese culture is also the oldest continuously surviving culture of this planet.

And, then there is a fourth culture, working with an ideogramatic writing system which has been around for a long time as well, although not as long as the Chinese - the Japanese culture in which the first calligraphic manuscript can be dated only back to 7th century AD. Considerably more recent, in other words. However, the Japanese visual tradition is so prolific and so sophisticated that there is more than enough reason to include its artifacts into this survey of the global history of visual communication design.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|

The Chinese Culture

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area, and can be under many diverse historiographical lenses. Classical Chinese civilization first emerged in the Yellow River valley during the Neolithic period. Chinese civilization can be traced as an unbroken thread many thousands of years into the past, making it one of the cradles of civilization.

China was first united under a single imperial state under Qin Shi Huang in 221 BCE. Orthography, weights, measures, and law were all standardized. Shortly thereafter, China entered its classical age with the Han dynasty (206 BCE – CE 220), marking a critical period, a term for the Chinese language is still "Han language", and the dominant Chinese ethnic group is known as Han Chinese. The Chinese empire reached some of its farthest geographical extents during this period. Confucianism was officially adopted and its core texts were edited into their received forms. Wealthy landholding families independent of the ancient aristocracy began to wield significant power. Han technology can be considered on par with that of the contemporaneous Roman Empire: mass production of paper aided the proliferation of written documents, and the written dialect of this period was imitated for millennia afterwards.

The Han dynasty was then followed by the Sui, the Tang and the Qing dynasties and the history of China culminated in the falling of the reign of dynasties (also due to the Opium wars wrought upon Chinese society by European colonialistic ambitions) to be replaced by the Modern Republic of China, which in its turn was replaced by a Communist regime under Mao Zedong, which evolved into the current economic super power that China is today.

The area in which the culture is dominant covers a large geographical region in eastern Asia. Important components of Chinese culture include calligraphy, ceramics, architecture, music, literature, martial arts, cuisine, visual arts, philosophy and religion. We start our survey on this page by looking at samples of Chinese calligraphy.

The ancient written standard was Classical Chinese which was expressed through an ideogramatic form of calligraphy, which was used for thousands of years by scholars who were deemed to be the top class of Chinese society, and who engaged in this noble art solely for intellectual reasons. In later times calligraphy became a commercialized enterprise as well, and works by famous artists became prized possessions.

Chinese literature has a long past; the earliest classic work in Chinese, the I Ching or "Book of Changes" dates to around 1000 BC. A flourishing of philosophy during the Warring States period produced such noteworthy works as Confucius's Analects and Laozi's Tao Te Ching.

The Tang Dynasty witnessed a poetic flowering, while the Four Great Classical Novels of Chinese literature were written during the Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368 - 1644/1644 - 1912 AD). Scholars sponsored by the empire commented on the classics in both printed and handwritten form. Royalty frequently participated in these discussions as well. Chinese philosophers, writers and poets were highly respected and played key roles in preserving the culture of the empire.

Publishing in the form of movable type was developed during the Song Dynasty (960 - 1279 AD).

It was said that on the day the characters were born, Chinese heard the devil mourning, and saw crops falling like rain, as it marked the beginning of civilization, for good and for bad.

The I Ching, or The Book of Changes, is an ancient divination text and the oldest of the Chinese classics. Originally a divination manual in the Western Zhou period, the I Ching was the basis for divination practice for centuries across the Far East, and eventually took on an influential role in Western understanding of Eastern thought. The images on the right show an edition of the book printed with movable type in the early 20th century.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |  |  |

|  |  |  |  |

Chinese art has arguably the oldest continuous tradition in the world, and is marked by a high degree of continuity within that tradition, reaching to today. Decorative arts are extremely important in Chinese art, and much of the finest work has been produced in large workshops or factories by unknown artists or artisans, especially in the field of Chinese porcelain. Much of the best work in ceramics, textiles and other techniques was produced in the imperial factories or workshops. Their outputs were used by the court and the upper classes, but were also distributed abroad on a huge scale to demonstrate the wealth and power of the Empire.

The tradition of Chinese ink and wash painting was practiced mainly by scholar-officials and court painters. The subject matter centered on landscapes, plants, and animals.

The genre developed aesthetic values depending on individual imagination and objective observation on behalf of the artist that are similar to those of the West; but that long predate the emergence of their Western counterparts.

Early Autumn, 13th century, by Song loyalist painter Qian Xuan.

Chinese Painting in the traditional style is known as guóhuà, meaning "native painting." Traditional painting involves the same techniques as calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black ink or colored pigments. As with calligraphy, the most popular materials on which paintings are made are paper and silk. The finished work can be mounted on scrolls, such as hanging scrolls or handscrolls. The two main techniques are:

-

Gongbi, meaning "meticulous," uses highly detailed brushstrokes. It is often highly colored and usually depicts figurative or narrative subjects.

-

Ink and wash painting, in Chinese shui-mo, is also known as "literati painting", as it was one of the "Four Arts" of the Chinese Scholar-official class. In theory this was an art practiced by gentlemen, a distinction that begins to be made in writings on art from the Song dynasty.

Chinese silk paintings

The architecture of China is as old as Chinese civilization itself. The Chinese have always enjoyed an indigenous system of construction that has retained its principal characteristics from prehistoric times to the present day. That this system of construction could perpetuate itself for more than four thousand years over such a vast territory and still remain a living architecture, retaining its principal characteristics in spite of repeated foreign invasions is a phenomenon comparable only to the continuity of the civilization of which it is an integral part.

|  |  |  |  |  |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |

A very important feature in Chinese architecture is its emphasis on articulation and bilateral symmetry, which signifies balance.

In this section we now finally come to the Crafts of China, which cover a wide gamut of different materials, ranging from different types of ceramics/porcelain, to jade, to wood and ivory carvings, to cloisonne. Of course, this is not all of it - there are also textile arts, landscaping, furniture design and much more. See the collection of the China Online Museum here and here.

Chinese Celadon ceramics.

Chinese Blue and White ceramics.

Two Chinese screens made out of embroidered silk.

Chinese jade objects and carvings.

Chinese cloisonne artifacts. This is an ancient technique for decorating metalwork objects with inlays of cut gemstones, glass, and enamel.

Chinese wood and ivory carvings. Since China had a very large repository of mammoth skeletons, ivory was considered to be an inferior element to jade. And of course, wood was held in similar disdain. Nevertheless, craftsmen produced these exquisite works from these "lowly" materials.

The Japanese Culture

Japan was settled about 35,000 years ago by Paleolithic people from the Asian mainland. At the end of the last Ice Age, about 10,000 years ago, a culture called the Jomon developed. Jomon hunter-gatherers fashioned fur clothing, wooden houses, and elaborate clay vessels. The culture of Japan has evolved over long millennia, from the country's prehistoric Jōmon period, to its current internationally acclaimed high-tech culture that absorbs influences from Asia, Europe, and North America. Buddhism came to Japan during the Asuka period, 538-710, as did the Chinese writing system. Japan's unique culture developed rapidly during the Heian era (794-1185). The imperial court turned out enduring art, poetry, and prose. The samurai warrior class developed at this time as well.

The inhabitants of Japan experienced a long period of isolation from the outside world during the Tokugawa shogunate between 1603 and 1868, which came about after the failed Japanese missions to Imperial China. Samurai lords, called "shogun," took over the government in 1185, and ruled Japan in the name of the emperor until 1868. Especially notable is the Edo period which lasted from 1603 to 1867 under Shogun rule since this would be the final era of traditional Japanese government, culture and society. Tokugawa Ieyasu’s dynasty of shoguns presided over 250 years of peace and prosperity in Japan, including the rise of a new merchant class and increasing urbanization. They also closed off Japanese society to Western influences. This isolation period lasted until the arrival of "The Black Ships" and the Meiji period; and bizarrely enough, accounts for a flourish in art and culture within Japanese society. In 1868 however, a new constitutional monarchy was established, headed by the Meiji Emperor and the power of the shoguns came to an end.

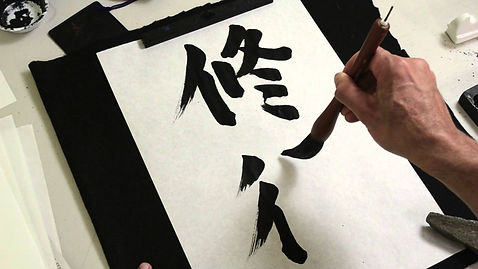

Japanese calligraphy, called shodō in Japanese, is a form of artistic writing of the Japanese language. After the invention of Hiragana and Katakana, the Japanese unique syllabaries, the distinctive Japanese writing system developed and calligraphers produced styles intrinsic to Japan.

Japanese painting is one of the oldest and most highly refined of the Japanese visual arts, encompassing a wide variety of genres and styles. As with the history of Japanese arts in general, the long history of Japanese painting exhibits synthesis and competition between native Japanese aesthetics and the adaptation of imported ideas, mainly from Chinese painting.

Of the many different styles and techniques with which Japanese painters expressed themselves - especially through silk screens and scrolls - on this page I wish to concentrate on only two techniques since these appear to me to be the two that distinguish themselves in reflecting something that is unique to the Japanese culture: Woodblock printing and sumi-e paintings.

The term ukiyo-e translates as "pictures of the floating world."

Woodblock printing, (moku-hanga) in Japanese, is a technique best known for its use in the ukiyo-e artistic genre of single sheets, but it was also used for printing books in the same period. The moku-hanga technique uses water-based inks—as opposed to western woodcut, which often uses oil-based inks. The Japanese water-based inks provide a wide range of vivid colors, glazes, and transparency.

The ukiyo-e genre of art flourished in Japan from the 17th through the19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk tales; travel scenes and landscapes; flora and fauna; and erotica.

Katsushika Hokusai, 1760 – 1849 was a Japanese artist, ukiyo-e painter and printmaker of the Edo period. Hokusai created the "Thirty-Six Views" both as a response to a domestic travel boom and as part of a personal obsession with Mount Fuji. It was this series, specifically The Great Wave print and Fine Wind, Clear Morning, that secured Hokusai’s fame both in Japan and overseas.

Utagawa Hiroshige, 1797 – 1858, was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition. Hiroshige is best known for his landscapes. The subjects of his work were atypical of the ukiyo-e genre, whose typical focus was on beautiful women, popular actors, and other scenes of the urban pleasure districts of Japan's Edo period. Hiroshige is especially noted for using unusual vantage points, seasonal allusions, and striking colors. During the Edo period, tourism was also booming, leading to increased popular interest in travel. Travel guides abounded, and towns appeared along routes such as the Tōkaidō, a road that connected Edo with Kyoto. In the midst of this burgeoning travel culture, Hiroshige drew upon his own travels, as well as tales of others’ adventures, for inspiration in creating his landscapes.

Sumi-e is the Japanese word for black ink painting, which was a technique of combining painting and writing that was initially developed in China. In this style emphasis is placed on the beauty of each individual stroke of the brush, a process of “writing a painting” or “painting a poem.” A great painting was judged on three elements: the calligraphy strokes, the words of the poetry and the ability of the painting strokes to capture the spirit of the text rather than a photographic likeness of what was described.

The tools which are essential for sumi-e painting are called the Four Treasures. These are the ink stick, ink stone, brush and paper.

The Crafts of Japan

Artisans of the Japanese culture have produced very strong output in many of the areas in which their Chinese colleagues were also active; notably so in porcelain and ceramics, but in other domains as well. However, despite the big Chinese influence that Japanese culture was under until the Edo period, Japanese artisans created unique artifacts and developed styles that were indigenous to their own culture. I will therefore not show output in genres that we have already seen in the survey on Chinese crafts above; but will concentrate on uniquely Japanese output, such as dry landscape gardens, wabi-sabi, ikebana, origami, and netsuke.

The Japanese rock garden or "dry landscape" garden creates a miniature stylized landscape through carefully composed arrangements of rocks, water features, moss, pruned trees and bushes, and uses gravel or sand that is raked to represent ripples in water. They were intended to imitate the intimate essence of nature, not its actual appearance, and to serve as an aid to meditation about the true meaning of life.

The term Wabi-Sabi represents a Japanese aesthetic philosophy that embraces authenticity over perfection. Characterized by asymmetry, irregularity, simplicity, economy, austerity, modesty and intimacy wabi-sabi values natural objects and processes as emblems of our transitory existence. Rust, woodgrain, freckles—the texture of life.

Wabi-Sabi is a beauty of things imperfect, impermanent and incomplete.

Ikebana is the Japanese art of flower arrangement in which the arrangement is a living thing where nature and humanity are brought together. It is steeped in the philosophy of developing a closeness with nature.

Netsuke are miniature sculptures that were invented in 17th-century Japan to serve a practical function. Traditional Japanese garments had no pockets; however, men who wore them needed a place to store their personal belongings. Their solution was to place such objects in containers hung by cords from the robes' sashes. The containers were held shut by sliding beads on cords. The fastener that secured the cord at the top of the sash was a carved, button-like toggle called a netsuke.

Origami (from ori meaning "folding", and kami meaning "paper") is the art of paper folding, which is associated with Japanese culture, where it has been practiced since the Edo period (1603–1867).

Lacquerware is a Japanese craft used within a wide range of fine and decorative arts. The material used is the sap of the urushi or lacquer tree that is native to Japan. The sap of this tree contains a resin that polymerizes and becomes a very hard, durable, plastic-like substance when it is exposed to moisture and air.

The Mesopotamians

Mesopotamia is a name for the area of the Middle Eastern Tigris–Euphrates river system, which is considered to be one of the cradles of Western civilization. Starting from the Bronze Age, Mesopotamia included the Sumerian, the Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian empires. In the Iron Age, the territory was controlled by the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian Empires. The Sumerians and Akkadians dominated the region from the beginning of written history (c. 3100 BC) to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC, when it was conquered by the Achaemenid Empire. Mesopotamia housed historically important cities such as Uruk, Nippur, Nineveh, Assur and Babylon, as well as major territorial states such as the city of Eridu, the Akkadian kingdoms, the Third Dynasty of Ur, and the various Assyrian empires.

Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the Neolithic Revolution from around 10,000 BC. It has been identified as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history including the invention of the wheel, the planting of the first cereal crops and the development of cursive script, mathematics, astronomy and agriculture."

The region was one of the four river civilizations where writing was invented, along with the Nile valley in Egypt, the Indus Valley Civilization in the Indian subcontinent, and the Yellow River in China.

It is in Mesopotamia that the world’s first cities were founded between 4000 – 3500 BC by the Sumerian people. Their daily lives were considerably different from those of the previous hunter-gatherer groups that wandered the world in a constant search for resources since these were settled societies whose mainstay revolved around agriculture. When it came to the urban population however, we encounter specialized professions. The cities were built upon complex irrigation and sewage systems, making civil engineering an important aspect of Mesopotamian culture. Other inventions were the plow, the wheel and sail boats, making food production, transportation and travel far more accessible than they ever were previously. A further area of expertise that was the result of the polytheistic belief system was astronomy, to the extent that contemporary astronomers are still aided by their discoveries.

Ziggurats were built by the ancient Sumerians, Babylonians, Elamites, Akkadians, and Assyrians for local religions. Each ziggurat was part of a temple complex which included other buildings.

Mesopotamian religion was polytheistic, thereby accepting the existence of many different deities, both male and female. Though the full number of gods and goddesses found in Mesopotamia is not known, but there around two thousand four hundred that we now know about, most of whom had Sumerian names.

The Mesopotamian gods bore many similarities with humans, and were anthropomorphic, thereby having humanoid form. Similarly, they often acted like humans, requiring food and drink, as well as drinking alcohol and subsequently suffering the effects of drunkenness, but were thought to have a higher degree of perfection than common men. They were thought to be more powerful, all-seeing and all-knowing, unfathomable, and, above all, immortal. One of their prominent features was a terrifying brightness which surrounded them, producing an immediate reaction of awe and reverence among men.

Mesopotamian religions are important to our discourse since the writing system of cuneiforms was developed as a consequence of it, practiced predominantly by Ziggurat priests who were also scribes.

Clay tablets with cuneiforms belonging to various Mesopotamian civilizations.

Cuneiform script, one of the earliest systems of writing, was invented by the Sumerians. It is distinguished by its wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets, made by means of a blunt reed for a stylus. The name cuneiform itself simply means "wedge shaped". The original Sumerian script was adapted for the writing of the Akkadian, Eblaite, Elamite, Hittite, Luwian, Hattic, Hurrian, and Urartian languages, and it inspired the Ugaritic alphabet and Old Persian cuneiform. Cuneiform writing was gradually replaced by the Phoenician alphabet during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911-612 BC). By the second century CE, the script had become extinct, and all knowledge of how to read it was lost until it began to be deciphered in the 19th century.

Inscriptions with cuneiforms belonging to various Mesopotamian civilizations.

Cylinder seals belonging to various Mesopotamian civilizations.

Alongside religious texts, cuneiforms were also used to record laws, like the Code of Hammurabi, as well as for recording maps, compiling medical manuals, among other uses. In time cuneiform literacy was not spread solely among the religious and administrative elite, but became common among average citizens also.

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian law code, dating back to about 1754 BC. It is one of the oldest deciphered writings of significant length in the world, and the first known legal code. The sixth Babylonian king, Hammurabi, enacted the code, and partial copies exist on a seven and a half foot stone stele and various clay tablets.

According to the Book of Genesis the Tower of Babel was a construct built by a monolingual humanity as a mark of their achievement: "Come, let us build ourselves a city, and a tower with its top in the heavens, and let us make a name for ourselves; otherwise we shall be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.' The result was that God punished them, for building a tower that reached to the sky, and wrecked their unified language into a myriad languages, upon which they could no longer communicate with one another.

The art of Mesopotamia rivaled that of Ancient Egypt as the most grand, sophisticated and elaborate in western Eurasia from the 4th millennium BC. The main surviving output is sculpture in stone and clay, some painted. Favorite subjects include deities, alone or with worshipers, and animals in several types of scenes: repeated in rows, single, fighting each other or a human, confronted animals by themselves or flanking a human or god in the Master of Animals motif, or a Tree of Life.

The famous Ishtar Gate, part of which is now reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, was the main entrance into Babylon, built in about 575 BC by Nebuchadnezzar II.

"War" panel of the Standard of Ur, ca. 2600 BC, showing parading men, animals and chariots.

The Assyrian Empire created a wealthier state than the region had known before, and very grandiose art in palaces and public places, no doubt partly intended to match the splendor of the art of the neighboring Egyptian empire. From around 879 BC the Assyrians developed a style of extremely large schemes of very finely detailed narrative low reliefs in stone or gypsum alabaster, originally painted, for palaces.

The Mesopotamian culture first started focusing on jewelry around 4000 years ago, initially in cities of Sumer and Akkad where this craft received much attention. Because of their immense wealth, jewel use was not confined only to nobility, royalty and religious leaders. Instead, the entire population accepted decorative items and jewels into their daily routine and everyone wore at least something decorative with themselves all the time.

The Egyptians

The temple of Karnak was known as Ipet-isu—or “most select of places”—by the ancient Egyptians. It is a city of temples built over 2,000 years and dedicated to the Theban triad of gods, Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. This derelict place is still capable of overshadowing many wonders of the modern world and in its day must have been awe-inspiring.

Ancient Egypt was a civilization of ancient Northeastern Africa, concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in what is now the modern country of Egypt. Egyptian civilization followed prehistoric Egypt and coalesced around 3150 BC with the political unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the first pharaoh Narmer. Egypt reached the pinnacle of its power in the New Kingdom, during the Ramesside period, after which it entered a period of slow decline when Egypt was invaded or conquered by a succession of foreign powers, until 30 BC, when, under Cleopatra, it fell to the Roman Empire and became a Roman province.

The success of the ancient Egyptian civilization came from its ability to adapt to the conditions of the Nile River valley for agriculture. The predictable flooding and controlled irrigation of the fertile valley produced surplus crops, which supported a more dense population, and social development and culture. With resources to spare, the administration sponsored mineral exploitation of the valley and surrounding desert regions, the early development of an independent writing system, the organization of collective construction and agricultural projects, trade with surrounding regions, and a military intended to defeat foreign enemies and assert Egyptian dominance. Motivating and organizing these activities was a bureaucracy of elite scribes, religious leaders, and administrators under the control of a pharaoh, who ensured the cooperation and unity of the Egyptian people in the context of an elaborate system of religious beliefs.

The many achievements of the ancient Egyptians include quarrying, surveying and construction techniques that supported the building of monumental pyramids, temples, and obelisks; a system of mathematics, a practical and effective system of medicine, irrigation systems and agricultural production techniques, the first known planked boats, faience and glass technology, new forms of literature, and the earliest known peace treaty, made with the Hittites.

Hieroglyphics, the ideogramatic writing technique developed by the ancient Egyptians, was used for many purposes, by priests and the nobility as well as the populace at large - from very mundane documents, such a laundry lists and shipping orders, to highly sophisticated religious and philosophical treatises. Their most beautiful usages are within a religious context, such as inscriptions and 'Books of the Dead.'

Hieroglyphics developed into a mature writing system used for monumental inscription in the classical language of the Middle Kingdom period; during this period, the system made use of about 900 distinct signs.

Chiseled hieroglyphics, created with sunken relief which is a technique that is largely restricted to the art of Ancient Egypt.

The image is made by cutting the relief sculpture itself into a flat surface. In a simpler form the images are usually mostly linear in nature, like hieroglyphs, but in most cases the figure itself is in low relief, but set within a sunken area shaped round the image, so that the relief never rises beyond the original flat surface. In some cases the figures and other elements are in a very low relief that does not rise to the original surface, but others are modeled more fully, with some areas rising to the original surface.

The technique is most successful with strong sunlight to emphasize the outlines and forms by shadow, as no attempt has been made to soften the edge of the sunk area, leaving a face at a right-angle to the surface all around it.

Egyptian Religion

To the Egyptians, the journey began with the creation of the world and the universe out of darkness and swirling chaos. Once there was nothing but endless dark water without form or purpose. Out of this chaos rose the primordial hill upon which stood the great god Atum was the grandfather to Osiris, Isis, Set, Nephthys, and Horus – the five Egyptian gods most often recognized as the earliest god-figures. Osiris showed himself a thoughtful and judicious god and was given rule of the world by Atum who then went off to attend to his own affairs. The one element which remains standard in all of of Egyptian mythology is the concept of harmony, Ma'at, which is disrupted and must be restored. The principle of Ma’at was at the heart of all of Egyptian mythology and every myth, in some form or another relies upon this value to inform it.

When the soul left the body at death, it was thought to appear in the Hall of Truth to stand before Osiris for judgement. The heart of the deceased was weighed on a golden scale against the white feather of Ma’at. If the heart was found to be lighter than the feather, the soul was allowed to move on to the Field of Reeds, the place of purification and eternal bliss. If the heart was heavier than the feather, it was dropped on to the floor where it was eaten by the monster Ammut (the gobbler) and the soul would then cease to exist. Although there existed a concept of the underworld, there was no `hell’ as understood by modern-day monotheistic religions. As Bunson writes, “The Egyptians feared eternal darkness and unconsciousness in the afterlife because both conditions belied the orderly transmission of light and movement evident in the universe.”

In order to help the deceased through this ordeal, a 'book of the dead' was complied during his/her lifetime, listing their virtues and good deeds, in order to sway the judgement process.

Egyptian Arts

Ancient Egyptian art reached a high level in painting and sculpture, and was both highly stylized and symbolic. It was famously conservative, and Egyptian styles changed remarkably little over more than three thousand years. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments and thus there is an emphasis on life after death and the preservation of knowledge of the past. Ancient Egyptian art included paintings, sculpture in wood (now rarely surviving), stone and ceramics, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, and other art media. It displays an extraordinarily vivid representation of the ancient Egyptian's socioeconomic status and belief systems.

For reasons that are not clear, although doubtless religious in origin, amulets in the form of scarab beetles were very popular in Ancient Egypt.

Ancient Egyptian sculpture was made out of many materials, including clay, bronze, gold and semi precious stones.

Egyptian jewellery.

And we end this survey of ancient Egyptian art and culture with this wonderful tomb fresco of an accountant in charge of grain at the great Temple of Amun at Karnak, named the Nebamun around 1350 BC. Here he is shown hunting birds in a small boat with his wife Hatshepsut and their young daughter, in the marshes of the Nile. Such scenes had already been traditional parts of tomb-chapel decoration for hundreds of years and show the dead tomb-owner "enjoying himself and seeing beauty," as the hieroglyphic caption here says.